[Home] [Archived news updates and letters]

|

News from Mark and Diane

Vanderkooi April 16, 2015 |

|

|

The

rhythmic throb of drums punctuated the wailing, and a cloud of dust

spiraled out the open tomb, up over the crowd into a blazing, cloudless

sky as young men shoveled the dry dirt onto the corpse. Chikina, was

being laid to rest after succumbing to something – you seldom really

know what – though in this case it might have been cancer or maybe

tuberculosis if his skeletal state 24 hours earlier was anything to go

by. As it happens, those 24 hours were the most important of his

modest life, which was otherwise distinguished by his skill in the

fabrication of the five-string harps which are the signature instrument

of Kwong music. Except insofar as we were in need of a harp (rarely), he

was little more than an acquaintance to us. So it came as a surprise

when Kaglo, one of our radio announcers, a dear friend, and a relative

of Chikina accosted Mark on the path yesterday and asked him to go see

Chikina, perhaps in the vain (though common) belief that there might

still be something the white missionary could do to save him. It

was a sad sight to behold. One could count every bone of his body under

the thin skin stretched over his almost comatose form. Deathbed conversions have a well-earned reputation of being

just a little too convenient, but then again, as someone once said,

there is nothing like impending death to focus the mind. Kaglo and Mark

judged they had nothing to lose if they spoke – and Chikina had much

to lose if they kept silent. They laid out the notions of atonement and

reconciliation to God to the apparently uncomprehending form lying

before them on a mat under a grass shelter. When they finished,

the form spoke – for a very long time in a barely audible, rasping

voice. Yes, he was ready. As he lay there, he made his appeal to

God in the name of Jesus, again for a very long time, and then Kaglo

(who with his typically Kwong bionic hearing actually understood what

Chikina had said) responded with his own appropriate prayer. Exactly 24

hours later, the dust billowed from his grave. But it was not the thought of Chikina’s death which kept us

awake at night. As Chikina’s body was failing him, we greatly feared

the death of the man who remains arguably our dearest friend and

confident in Kwongland, Pastor Moses Wanang, also affectionately

known in Mark’s older newsletters as “Old Moses.” In the

end, it looks like his tale will have a happier ending (at least from a

human standpoint) than that of Chikina, thanks in no small measure to

the graciousness of the Adventist pilot who dropped everything to

evacuate him, and to the timely treatment and blood transfusions given

by the doctors at the Adventist hospital. Life and death here has none of the sterility, none of

professionalism, none of the decorum which blesses it – and perhaps

curses it – at home. It is earthy, ubiquitous, and often filled with a

pathos which westerners can scarcely comprehend – exemplified in

today’s events by Chikina’s son who sat alone, weeping

uncontrollably as they buried his father, completely ignored by 300

bystanders whose presence was ostensibly to comfort the bereaved. While

we don’t enjoy the tension, the sleepless nights, and the frequent

sense of helplessness, we would not, given a choice, trade them for a

more domesticated life (though it would be a tempting proposition

nevertheless). For by them, the real realities of the universe are

constantly thrust before our eyes, and we are, it seems (or at least we

hope), much the richer in our souls because of it. |

Chikina

in life

Chikina

in death

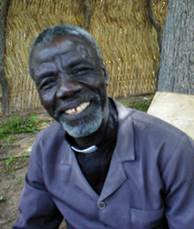

Pastor

Wanang |

|

|

|