|

If we are so foolish as to call ourselves "Bible

Translators", then we shouldn't be surprised that people tend to think that

we actually just sit down and translate just like you might, say, sit down and

work a crossword puzzle. Alas, it's a whole lot more complicated than that for a

number of reasons. Two reasons, to be precise.

First, no white person can or will ever learn to speak Kwong like a native.

This is no reflection on either the mental capacity of white people, nor on the

complexity of Kwong (which is not an exceptionally difficult language by world

standards). Rather, it is a reflection on the inherent complexity of any human

language. Human thought is unbelievably complex, and the language which it

spawns is correspondingly complex. So there you have it - no matter how well we

learn the language, we can never express it with all the breadth and richness of

a native speaker.

Second, while it would be going too far to say that a Kwong man or woman could

never learn to exegete a Biblical text, read commentaries in

English and French, struggle with the nuances of theology and Judeo/Greek

thought, and synthesize what he learns in such a way as to translate it, the

fact of the matter is that none have, and it is unlikely that any will.

So, the Kwong need us, and we are handicapped without them. Just the kind of

interdependence you might expect God to arrange so that none of us gets too

cocky.

So here's how it works:

-

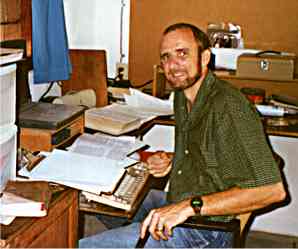

Exegesis

and Front Translation -Mark studies the passage to be translated,

consults commentaries and other reference works, and produces a French

version of the passage which expresses the meaning in terms that the

translators can understand. Mark tries to anticipate the problems which

might arise in Kwong and suggests key Kwong words where helpful.

-

Initial

Kwong Translation -

Using the French version Mark has produced, Laurent produces an

initial Kwong draft of the passage.

-

Cross-examination - Laurent

reads the Kwong draft to Mark who follows along in other versions.

Mark critiques the translation and together they work out those places where

the translation is either unnatural, unclear, or departs from the meaning of

the original. Cross-examination - Laurent

reads the Kwong draft to Mark who follows along in other versions.

Mark critiques the translation and together they work out those places where

the translation is either unnatural, unclear, or departs from the meaning of

the original.

At this point we call it a "First Draft." Luke takes the

manuscript and types it, and then we usually use the translated passage in a

discipleship class where it gets its initial “road-test”.

-

1st

Field Test -

One or more people from the village who were not involved in the translation

are called in as "guinea pigs" to test the translation. Luke or Joseph reads

the draft translation out loud, while the "guinea pig" translates what he

hears into French. Mark follows along in other versions and then

cross-examines the guinea pig on what he understands from the passage as we

have translated it. It is very surprising what variety of serious

misunderstandings show up in this way.

-

Recheck

Exegesis

- By

this time the initial draft has undergone so much revision, it is

questionable as to just how faithful the translation still is. Mark goes

over it all again with his commentaries and reference works to make sure we

haven’t wandered off into some fiction not in the original text nor inadvertently invented a new religion.

-

2nd

Field Test

- The

passage is once again tested with yet another "guinea pig" to make sure that

the changes introduced by the 1st testing or in the exegesis

check did not mess something else up.

-

Consultant

Check -

The final quality-control is performed by a consultant who is an experienced

Wycliffe translator. (The Swiss lady who presently checks our work has two New

Testaments to her name.) Most of the Bible Societies require such a check

before they’ll publish anything. It’s a bit complicated and pretty

tedious since the consultant doesn’t know Kwong, but over the years a very

effective system has been worked out which is similar to what we do for our

field testing.

-

Publishing

- Once the consultant gives his/her approval, we feel free to publish. For

Scripture portions, the final “textus receptus” is formatted, and sent

to the TEAM printshop in Moundou. We sell the material at about half cost

(and, incidentally, are always interested in having some money on hand

to cover the other half). When the time comes to print the whole Bible (or a

substantial part of it) we will doubtless work through one of the big Bible

Societies.

|

Cross-examination

Cross-examination